Riding the Rails: Hope and Survival During the Great Depression's Darkest Days

The Great Depression was one of the toughest times in American history. The stock market crash of 1929 sent shockwaves through the country, leaving millions of people jobless and struggling to make ends meet. Factories closed, farms dried up, and breadlines grew long as families faced poverty and uncertainty. During this time, a unique survival strategy emerged: riding the rails. Thousands of men, women, and children took to the freight trains, searching for work, food, and a glimmer of hope.

Let's explore the phenomenon of riding the rails during the Great Depression—how it became a symbol of hope, survival, and the resilience of the human spirit during America's darkest days.

The Rise of Hobos

In the 1930s, a new class of wanderers emerged on the American landscape: the hobos. The word "hobo" wasn't new, but the phenomenon reached its peak during the Depression. Hobos were people who left their homes, families, and communities to travel in search of work. They differed from "tramps," who traveled but didn't work, and "bums," who neither traveled nor worked. Hobos were often willing to work, but opportunities were scarce, forcing them to move from place to place.

Why did so many people choose this dangerous, transient lifestyle? Simply put, there were no other options. By 1932, unemployment in the U.S. had skyrocketed to 25%, with nearly 13 million people out of work. Cities and towns couldn't provide enough jobs or public assistance, so people turned to the rails as a way to reach new towns, hoping to find a job or at least a hot meal.

It wasn't just single men who rode the rails—fathers, sons, and even entire families sometimes took this journey. While most hobos were men, women and children rode the trains, all desperate for a chance at survival.

The Dangers of Riding the Rails

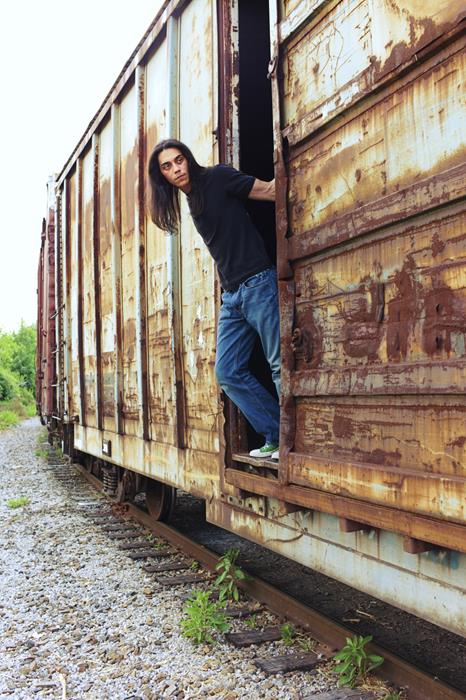

Hopping on a freight train wasn't just as simple as boarding. Riding the rails was fraught with danger. First, there was the physical risk. People had to sneak onto moving trains or hide in rail yards to avoid detection by railroad police, known as "bulls." These bulls were notorious for their brutality, sometimes beating or even killing those caught trespassing.

In addition to the bulls, there were the trains themselves. Climbing onto a moving train was risky—people could fall and be maimed or killed by the heavy wheels. Once aboard, the trains offered little comfort. Hobos often clung to the tops of boxcars or huddled inside cold, dirty freight cars.

The weather was another enemy. The harsh winters and scorching summers make the journey even more grueling. Yet, despite these dangers, people kept riding because it offered a lifeline to something better, even if just temporarily.

One key factor that made this phenomenon possible was the vast network of railroads crisscrossing the U.S. During the 1930s; the railroad system was the backbone of American transportation. With over 400,000 miles of track, the railroads connected cities, towns, and rural areas, allowing hobos to move across the country in search of new opportunities.

The Hobo Culture and Support Networks

Despite their transient lifestyle, hobos developed a rich culture. There was even a kind of "code" they lived by—both literally and figuratively. The hobo code was a set of symbols drawn on fences, walls, or buildings to communicate with other travelers. For example, a smiling cat meant a kind-hearted woman lived nearby, while a picture of a cross signaled that the people living in the house were religious and might help with food or shelter.

Hobo communities, known as "jungles," sprang up near railroad lines or on the outskirts of towns. These makeshift camps provided a temporary place to rest, share stories, and pool resources. In these jungles, hobos would exchange tips on which towns were worth visiting for work or which ones were best to avoid due to hostile locals or harsh police.

Interestingly, while the Great Depression tore many communities apart, the hobo jungles represented a form of solidarity. These camps were places where people from all walks of life—displaced farmers, factory workers, teenagers, and even some professionals—came together to survive. They shared what little they had and looked out for one another. A unique blend of resilience and mutual aid emerged from the hardship.

Impact on Families and Society

The decision to ride the rails had a profound impact on American families. Fathers and sons often left home in search of work, leaving their families behind. For many, this separation was heart-wrenching, as they didn't know when—or if—they would be able to return. Some never came back.

In other cases, entire families took to the rails. A famous example is Woody Guthrie, the folk singer who grew up during the Depression and traveled across the country by hopping trains. His songs captured the hobo life's spirit and ordinary Americans' struggles during the Depression. Guthrie's "This Land is Your Land" is one of the most iconic songs from that era, reflecting the hope and perseverance of the American people.

While some people viewed hobos with sympathy, many saw them as a threat or nuisance. In some towns, hobos were welcomed with a meal and a place to sleep; in others, they were chased away by local law enforcement or vigilante groups. This mixed reception highlighted the tension between those who were suffering from the Depression and those who feared the consequences of so many desperate, wandering people in their communities.

Stories of Survival and Resilience

For many hobos, riding the rails wasn't just about finding a job but about survival. Some managed to find work as migrant laborers, doing seasonal farm work or construction jobs. Others did odd jobs in exchange for food or shelter. Still, others found themselves caught in a cycle of poverty, always on the move but never finding the stability they sought. Despite the hardships, riding the rails provided a lifeline and a glimmer of hope for those who had lost almost everything.

Amid the struggle, there were also stories of hope and resilience. Many hobos formed lasting friendships on the road, supporting one another through some of the darkest times in American history. Some travelers even discovered new opportunities that changed their lives.

One of the most famous examples of a rail rider who turned his fortunes around is Jack London, who, in the 1890s—long before the Depression—rode the rails as a young man in search of adventure. London's experiences as a hobo later inspired much of his writing, giving voice to the oppressed and displaced. His story reflects the idea that, while life on the rails was harsh, it could also be transformative, giving individuals new perspectives and opportunities.

However, for many Depression-era hobos, survival on the rails was less about adventure and more about finding a way to live day-to-day. The documentary Riding the Rails(1997) by Lexy Lovell and Michael Uys paints a vivid picture of the young people who took to the trains during the Great Depression. The film tells the stories of teenagers who, like Jack London, left their homes out of necessity rather than wanderlust. Through firsthand accounts, the documentary captures the real struggles, dangers, and moments of hope experienced by those who rode the rails.

For example, Ed Paulson, featured in the film, left home at the age of 14 to search for work and food. His story is a testament to the resilience of many young hobos who faced hunger, loneliness, and danger. Like many others, he forged lasting bonds with fellow travelers, sharing what little they had to make it through another day.

The film also shows women who took to the rails, like Peggy De Hart. Her journey was fraught with unique challenges and risks, reflecting the additional dangers that women hobos faced. Yet, like her male counterparts, De Hart persevered, demonstrating the indomitable spirit that so many hobos possessed.

Despite the bleakness, Riding the Rails emphasizes that many of these travelers gained survival skills and a renewed sense of community and hope. Some found work in new towns, while others gained life experiences that would stay with them forever. For many, the lessons learned on the rails—of resourcefulness, mutual aid, and resilience—became lifelong virtues.

Though not everyone found success, by the late 1930s, as the New Deal programs under President Franklin D. Roosevelt began to take effect, many hobos could return home or settle down. These government initiatives helped create jobs and rebuild the economy, offering a glimmer of hope to those who had spent years wandering the country in search of better opportunities.

The Legacy of Riding the Rails

The phenomenon of riding the rails left a lasting mark on American culture. Hobos became part of the national folklore, and their stories are told in songs, books, and films. Woody Guthrie's music, for instance, immortalized the hobo life and the struggles of the working class during the Depression. His songs inspired generations of musicians and activists, reminding people of the hardships faced by those who lived through the 1930s.

The experience of riding the rails was also captured in books like "Bound for Glory" by Guthrie and "The Road" by Jack London. These stories shed light on the lives of ordinary people who, despite overwhelming odds, refused to give up. They survived through resourcefulness, grit, and the hope that things would get better.

Though the hobo lifestyle faded after the Depression, it remains an iconic part of American history. It reminds us of the lengths people will go to in search of hope during dark times.

Conclusion

Riding the rails during the Great Depression wasn't just about physical survival but about holding onto hope in the face of overwhelming adversity. Hobos, with their makeshift communities, shared symbols, and unwritten codes of conduct, represented a resilience that helped them endure one of the hardest periods in American history. While the era of the hobo may have passed, their legacy remains a testament to the power of human perseverance and the search for a better life, even when the odds seem impossible.

In the darkest days of the Great Depression, the rails carried not only freight but also the dreams of countless Americans, desperate for a glimmer of hope on the horizon.