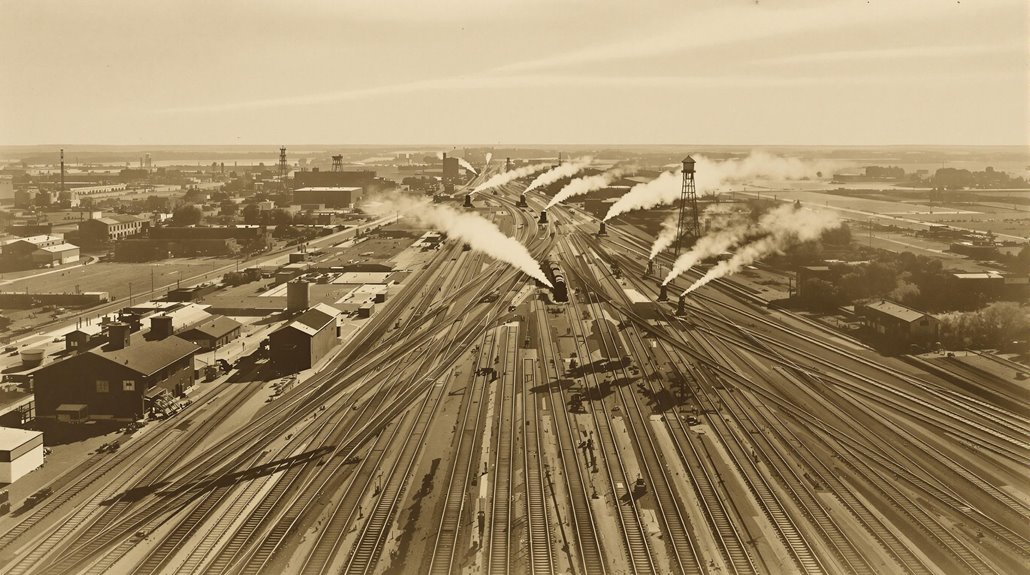

How Many Miles of Railroad Were There in the US in the 1920s?

Throughout the 1920s, you'll find that the U.S. maintained over 250,000 miles of railroad track across the country. The network had reached its historic peak in 1916 with 254,037 miles, before slightly declining to 252,360 miles by 1929. This extensive system connected major cities from coast to coast, with the heaviest concentration in the Northeast and Midwest regions. The story behind this massive network reveals fascinating details about America's transportation evolution.

Railroad Network Expansion Through The 1920s

While railroad construction boomed in the early 1900s, reaching its peak of 254,037 miles in 1916, the 1920s marked a significant slowdown in track expansion. You'll find that between 1910 and 1919, the railroad industry added 19,205 miles of new track in its last major growth period.

However, the pace drastically changed in the following decade. From 1920 to 1929, railroad construction only added about 6,000 new miles to the network. This dramatic slowdown wasn't surprising, as you'd notice the rising popularity of automobiles and trucks began affecting both passenger traffic and freight traffic. The declining demand for rail transportation meant there was less need for network expansion.

By 1929, the total railroad mileage had actually decreased slightly to 252,360 miles from its 1916 peak. Major carriers like Pennsylvania Railroad System remained crucial for freight transport despite the slowdown in track expansion.

Peak Mileage Statistics And Record Years

Although the U.S. railroad network expanded continuously through the early 1900s, it reached its historic peak of 254,037 miles in 1916. After this milestone, you'll notice that railroads began a gradual decline in total mileage, dropping to 251,890 miles by 1920.

This pattern wasn't unique to standard railroads - the interurban electric railway network also hit its peak in 1916 with 15,580 miles of track.

The decline affected both types of rail transportation systems, with interurban mileage falling to 15,337 miles by 1920. Despite these reductions, you'd still find an impressive network of over 250,000 miles of track across the country throughout the 1920s, making it one of the most extensive railroad systems in American history. The extensive rail network continued to serve as a crucial backbone for industrial growth, facilitating the swift movement of raw materials and finished products between factories and markets.

Regional Distribution Of Rail Lines

The geographic spread of America's railroad network in the 1920s revealed stark regional differences in development and coverage. You'd find the most extensive track mileage in the Northeast and Midwest, where over 100,000 miles of rail lines served these industrialized regions. The West, including its crucial transcontinental routes, maintained roughly 80,000 miles of track, while the South lagged behind with approximately 50,000 miles of rail infrastructure.

The Great Plains stood out with its well-developed regional railroad system, efficiently connecting agricultural centers to major transportation hubs. These regional variations depict a clear illustration of America's uneven railroad development, with the Northeast and Midwest dominating the nation's total mileage. While the country's overall rail network peaked at 254,000 miles in 1916, you could still see these regional disparities throughout the 1920s.

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 had been instrumental in establishing these extensive networks, reducing cross-country travel time from months to less than a week.

Impact Of Government Regulation On Track Growth

Despite increasing government oversight, America's railroad expansion reached its pinnacle in 1916 with 254,037 miles of track before beginning a steady decline. The Mann-Elkins Act first imposed strict regulations on rail service in 1910, requiring American Railway companies to justify their passenger rates to the Interstate Commerce Commission. You'll find this marked a turning point, as the Great era of new track construction slowed dramatically.

After the Union Pacific and other major rail companies lost their first-generation leaders in the 1910s, their successors wielded less political influence. This power shift, combined with tighter government controls and rising competition from automobiles, led to minimal track expansion in the 1920s. While the previous decade saw over 19,000 miles of new construction, the 1920s added just 6,000 miles of track to America's rail network.

Economic Factors Affecting Rail Development

Economic turbulence marked rail development throughout the 1920s as America's railroads faced mounting pressures from multiple fronts. You'll find that the rise of automobiles and trucks created unparalleled competition, causing significant declines in both passenger rail and freight rail service.

The Interstate Commerce Commission's control over freight rates complicated matters, as railroads couldn't easily adjust prices to meet rising costs and competitive pressures.

While the federal government's return of the rail network to private control offered hope, the reality proved challenging. The Esch-Cummins Act encouraged consolidation to improve efficiency, but these efforts fell short of expectations.

When the Great Depression hit in the 1930s, it delivered another blow to the already struggling industry, forcing widespread abandonments and further consolidation of America's rail infrastructure.

Competition From Emerging Transportation Modes

Rising competition from automobiles and trucks marked a crucial period for America's railroads in the 1920s. You'll find that the automobile industry gained significant momentum after the Ford Model T's 1908 debut, altering how Americans viewed transportation modes. The Federal Aid Road Act's $75 million investment in roadway improvements further accelerated this shift.

Railroad companies faced mounting pressure as they struggled with regulatory challenges that prevented them from raising freight rates to match rising costs. When you consider their difficulties handling World War I traffic demands, combined with growing competition from motorized vehicles, you can understand why many railroads faced financial trouble.

These pressures ultimately led numerous rail companies into defaults and receiverships during the 1920s, as regulation continued to limit their ability to adapt to the changing transportation landscape.

Railroad Infrastructure Investment Patterns

The peak of American railroad infrastructure arrived in 1916 with 254,037 miles of track, marking the end of rail's major expansion era. You'll find that railroad companies invested heavily in the network during the 1910s, adding 19,205 new miles between 1910-1919.

However, the railroad industry's growth pattern changed dramatically in the following decade. During the 1920s, new railroad construction slowed considerably, with only 6,000 miles added to the network. American railroads were affected by rising operational costs that outpaced inflation, while the Interstate Commerce Commission denied their requests for freight rate increases.

The interurban rail mileage peaked alongside the main network in 1916 at 15,580 miles before declining. While some short lines were built, the overall rail mileage began shrinking as the industry faced financial pressures.

Track Abandonments And Line Consolidations

While railroad mileage had reached its pinnacle in 1916, track abandonments began accelerating throughout the 1920s as companies faced mounting pressures from automotive competition. You'll notice that only 6,000 miles of railroads were built during the 1920s, compared to over 19,000 in the previous decade. Rail service declined sharply as constructed networks proved unprofitable, particularly affecting interurban electric lines.

The situation worsened during the Great Depression when many companies were forced to consolidate or abandon tracks. Even major players like the Great Northerns couldn't maintain all their routes for freight and passengers. Wall Street's influence and changing economics of rail transportation led to significant network reductions. Later, the Staggers Rail Act in the 1970s-80s gave railroads more freedom to abandon unprofitable lines and streamline their operations.

Geographic Coverage And Service Areas

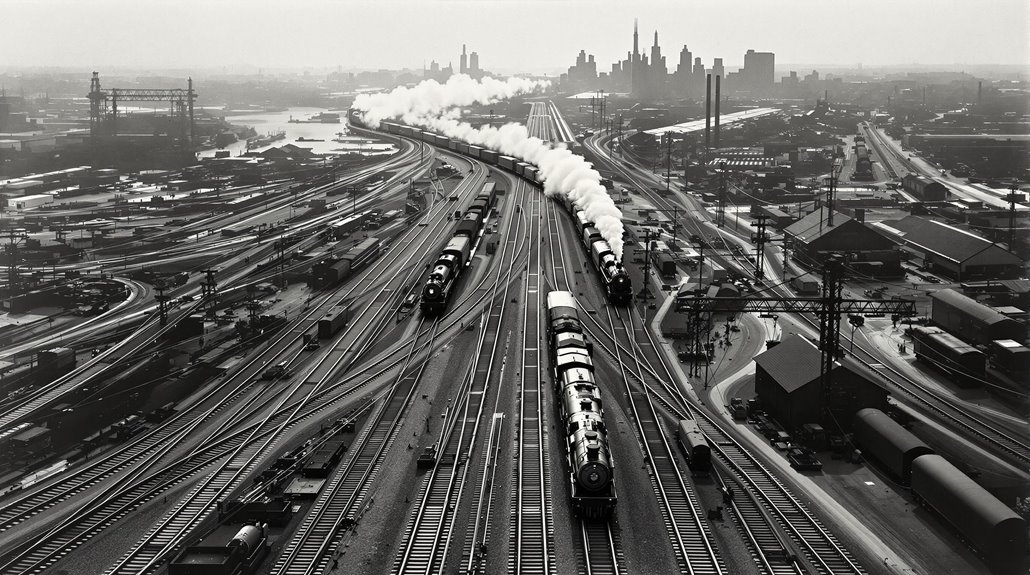

Just how far did America's iron horse reach in the 1920s? You'd find passenger trains connecting nearly every major city, from New York City to San Francisco. The first transcontinental railroad, built by the Union Pacific Railroad, had already altered coast-to-coast travel by this time.

Major carriers like the New York Central and Baltimore and Ohio Railroad dominated the Northeast and Midwest, where you'd see the densest network of tracks serving industrial hubs. While the South had fewer miles of track, you could still reach most agricultural centers and ports by rail. The United States Railroad Administration had overseen the nation's rail system during WWI, and though some lines would later become part of Consolidated Rail, the 1920s network still covered about 240,000 miles, reaching virtually every corner of America.

Railroad Construction And Maintenance Trends

Railroad construction reached its pinnacle in 1916 with an impressive 254,037 miles of track crisscrossing America. You'll find that rail transportation experienced dramatic changes in the following decades as new transportation modes emerged.

The 1910s marked the last major railroad construction boom, adding 19,205 miles of new track. Interurban railways peaked at 15,580 miles in 1916 before declining after 1918. The 1920s saw only 6,000 new miles built as competition from automobiles increased. The Great Depression dealt another blow to the railroad industry in the 1930s.

Railroad maintenance suffered during these challenging times, and many smaller railroads faced bankruptcy as the industry adapted to changing economic conditions and transportation preferences.