Railroads in the 1930s: Resilience Amid the Great Depression

The 1930s were a decade of hardship for many industries, but few faced challenges as monumental as the railroad industry. With the onset of the Great Depression, railroads—once a dominant force in American transportation—struggled to stay afloat. Freight and passenger numbers plummeted, financial woes mounted, and fierce competition emerged from automobiles and trucks. Yet, despite these obstacles, the railroads displayed remarkable resilience. Through innovation, adaptation, and a steadfast commitment to keeping America moving, the railroads not only survived the 1930s but also laid the groundwork for future growth.

Railroads in a Time of Crisis

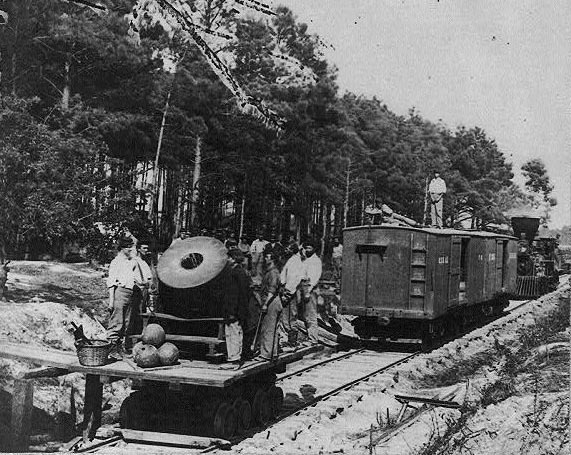

Before the Great Depression, railroads were the backbone of American transportation. They moved goods across the country, enabling people to travel long distances relatively easily. In the early 20th century, railroads were crucial to the economy, linking cities, industries, and communities in ways that shaped modern America. The railroad industry was a symbol of progress, connecting the vast American landscape and fueling industrial growth.

However, the stock market crash of 1929 set off a chain reaction that hit the railroad industry hard. As the economy spiraled downward, businesses produced fewer goods, and people had less money to spend on travel. The result was a sharp drop in freight shipments and passenger travel on trains. By the early 1930s, many major railroad companies were in dire straits, with some even filing for bankruptcy. The once-mighty industry, which had previously thrived during periods of expansion and industrialization, was teetering on the brink.

Facing Financial Struggles and New Competition

The financial toll on the railroads during the Great Depression cannot be overstated. Major companies like the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central Railroad, which had once been industry giants, saw their revenues plummet. Railroads were often highly leveraged, relying on borrowed money to expand and maintain tracks, rolling stock, and infrastructure. When the economic collapse hit, their revenues couldn't support these debt obligations, leading many to default on loans or declare bankruptcy. Bankruptcies were not uncommon, as railroads struggled under the weight of massive debts and reduced demand.

Adding to their woes, railroads faced increasing competition from the burgeoning automobile industry. Cars, especially Henry Ford's affordable Model T, were becoming more common in American households. By the late 1920s and early 1930s, cars were no longer a luxury item for the wealthy but had become a viable transportation option for the middle class. As car prices dropped and road infrastructure improved, more Americans opted for the freedom and convenience of personal vehicles. This shift meant fewer train passengers and less reliance on railroads for local transportation.

Trucks also emerged as formidable rivals to railroads in the freight business. Once restricted to local deliveries, trucks became more capable of long-distance hauls thanks to advancements in highway construction and truck technology. Innovations in rubber tires, better roads, and the mass production of vehicles made trucks a more viable option for moving goods across the country. This shift presented another blow to railroads, which had long dominated the transportation of goods across the country.

By the early 1930s, passenger train travel had significantly decreased. In 1916, railroads had carried around 1 billion passengers. By 1930, that number had dropped to 700 million, and it continued to fall as cars and buses became more popular. Trains also lost ground in the freight sector. Trucks began to chip away at the railroads' share of freight transportation, moving an increasing amount of goods that had traditionally traveled by rail.

The Streamliner Revolution

Faced with this mounting pressure, railroads needed to adapt quickly. One of the most significant innovations of the 1930s was the introduction of streamliner trains. These sleek, modern trains were designed to capture the public's attention and reignite interest in rail travel. The streamliners were faster, more efficient, and far more attractive than their predecessors.

Union Pacific's "M-10000," introduced in 1934, was among the first of these new trains. Painted in a striking yellow and brown color scheme, the M-10000 could reach impressive speeds of up to 110 miles per hour, making it a marvel of modern engineering. Its futuristic design featured lightweight materials and aerodynamically smooth lines, a stark contrast to the bulky, slow-moving steam locomotives of the past. It was an instant hit, offering passengers a fast and stylish alternative to cars and buses.

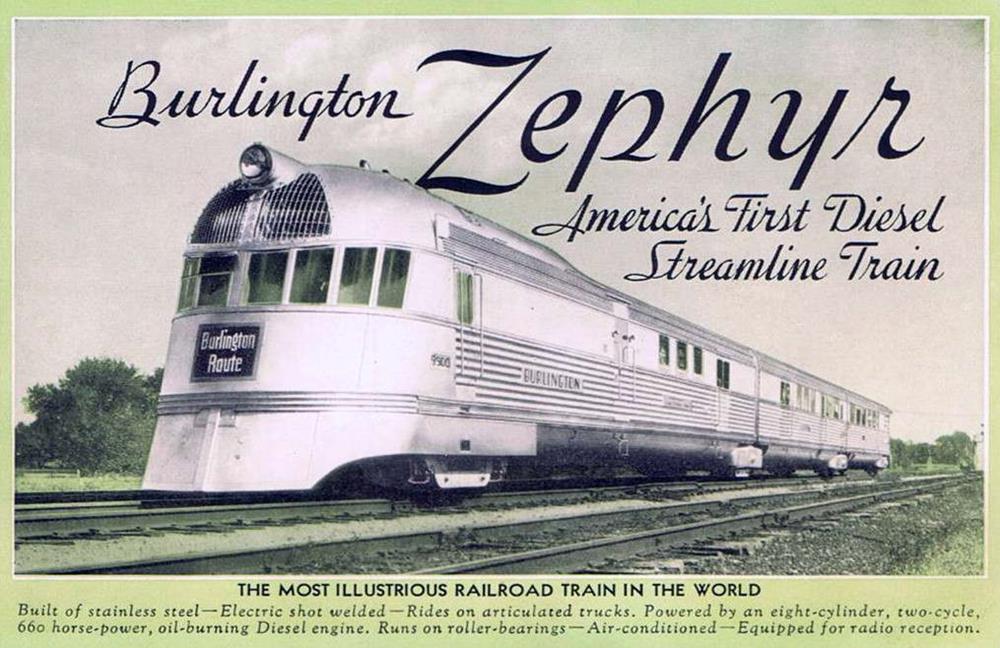

Not to be outdone, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad introduced the Zephyr 9900, a stainless-steel marvel that symbolized the future of rail travel. In May 1934, the Zephyr made a famous non-stop run from Denver to Chicago, covering 1,015 miles in just over 13 hours. This event, which became known as the "Dawn-to-Dusk" run, was a media sensation, with newspapers and radio broadcasts covering the train's journey in real-time. The Zephyr's successful journey highlighted the technological advancements of streamliners and showcased the speed and efficiency of modern rail travel.

Streamliners weren't just about speed – they represented a new philosophy of rail travel. They were designed with the passenger experience in mind, offering greater comfort, convenience, and efficiency. Streamliners often featured air-conditioned cars, comfortable seating, and improved dining options, making train travel more enjoyable and luxurious. As more railroads adopted these trains, streamliners helped revitalize the industry and restore some of the public's faith in rail travel.

Technological Shifts: From Steam to Diesel Power

While the sleek appearance of streamliners captured headlines, another quieter revolution was taking place within the railroad industry: the shift from steam to diesel engines. Steam engines had been the workhorses of the railroads for decades, but by the 1930s, their time was coming to an end.

Diesel engines were more efficient, reliable, and cost-effective than steam engines. General Electric pioneered the development of diesel technology as early as 1918, but it wasn't until the 1930s that diesel engines began to see widespread use. Initially, diesel engines were employed in train yards to switch cars and perform other support tasks.

However, the real breakthrough came in 1935 when the Electro-Motive Corporation (EMC) introduced its first diesel-electric locomotives for mainline railroads. Several major railroads, including the Santa Fe and the Baltimore & Ohio, quickly adopted these powerful engines, which used them for long-haul freight operations.

Diesel engines offered several advantages over steam. They were easier to maintain, required fewer crew members to operate, and consumed less fuel. As a result, diesel engines helped railroads reduce costs and improve efficiency during a time when every penny counted.

One of the most significant advancements in diesel technology came with EMC's FT locomotive, introduced in 1939. The FT was a game-changer, capable of producing 5,400 horsepower through its modular design. Its success helped accelerate the transition from steam to diesel power, and by the 1940s, diesel locomotives had become the standard for many railroads.

The adoption of diesel engines was part of a broader trend of modernization in the railroad industry. By embracing new technology and streamlining their operations, railroads cut costs and improved service, ensuring their survival during the difficult years of the Great Depression.

The Adaptation and Survival of Railroads

The Great Depression was a defining moment for the railroad industry, but the companies that survived did so by adapting to the new realities of the time. In addition to streamliners and diesel engines, railroads implemented a range of strategies to stay competitive.

One approach was to cut costs by reducing services on unprofitable routes and laying off workers. Many railroads also slashed fares to attract more passengers, even if it meant operating at a loss in the short term. Additionally, railroads worked to improve the efficiency of their operations, investing in better infrastructure and equipment to reduce overhead.

Collaboration with the federal government also contributed to the railroads' survival. Several New Deal programs aimed at stimulating the economy indirectly benefited the railroad industry. Public works projects funded by the government helped improve railroad infrastructure, including bridges, tunnels, and rail lines. Additionally, the federal government recognized the importance of railroads to the nation's economy and provided subsidies and financial assistance to help struggling companies stay afloat.

Despite the challenges, railroads remained essential to the U.S. economy throughout the 1930s. Freight trains continued to move vital goods across the country, from agricultural products to industrial supplies. Though reduced in number, passenger trains still provided a critical link between cities and rural communities. Railroads were the lifeblood of many small towns and rural areas, where access to other forms of transportation was limited.

The Role of Railroads in Economic Recovery

By the late 1930s, as the U.S. economy began to recover, and railroads helped support that recovery. The revival of industries such as manufacturing and agriculture meant an increased demand for freight transportation, and railroads were uniquely positioned to meet that need.

As factories ramped up production, railroads transported raw materials to manufacturing centers and distributed finished goods to markets across the country. In many ways, railroads were the unsung heroes of America's recovery, keeping the economy moving even in the toughest times.

The railroads' contribution didn't end there. As the country inched closer to World War II in the late 1930s, railroads became even more critical to national defense. Railroads transported troops, military supplies, and raw materials needed for the war effort. By the time the war broke out, railroads were once again at the forefront of America's transportation system.

Conclusion

The railroads of the 1930s faced immense challenges, from financial struggles to intense competition from new forms of transportation. Yet, through innovation and adaptation, they survived and laid the foundation for a brighter future. The introduction of streamliners, the shift to diesel power, and the determination to provide essential services to a struggling nation all contributed to the railroads' resilience.

In many ways, the story of railroads in the 1930s is one of survival against the odds. It shows the importance of adaptation and innovation in the face of adversity. By the end of the decade, the railroads had weathered the storm of the Great Depression and were ready to take on the new challenges of the coming decades. Their legacy continues to shape the transportation landscape today, reminding us that even in the hardest times, resilience can lead to success.